which james bond movie had the same name as a british national lottery draw?

| James Bond | |

|---|---|

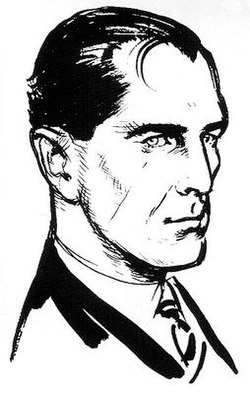

Ian Fleming's image of James Bail; commissioned to aid the Daily Express comic strip artists | |

| Created by | Ian Fleming |

| Original piece of work | Casino Royale (1953) |

| Print publications | |

| Novel(s) | List of novels |

| Short stories | See listing of novels |

| Comics | List of comic books |

| Comic strip(s) | James Bond (1958–1983) |

| Films and television | |

| Flick(s) | Listing of films |

| Short film(southward) | Happy and Glorious (2012) |

| Tv set series | "Casino Royale" (Climax! season 1 - episode three) (1954) |

| Blithe series | James Bond Jr. (1991–1992) |

| Games | |

| Traditional | Various |

| Role-playing | James Bond 007: Role-Playing In Her Majesty's Hole-and-corner Service |

| Video game(s) | List of video games |

| Audio | |

| Radio program(s) | Radio dramas |

| Original music | Music |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Toy(s) | Various |

| Portrayers |

|

The James Bond series focuses on a fictional British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by author Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two brusk-story collections. Since Fleming's death in 1964, eight other authors have written authorised Bond novels or novelisations: Kingsley Amis, Christopher Wood, John Gardner, Raymond Benson, Sebastian Faulks, Jeffery Deaver, William Boyd, and Anthony Horowitz. The latest novel is Forever and a Day by Anthony Horowitz, published in May 2022. Additionally Charlie Higson wrote a series on a immature James Bond, and Kate Westbrook wrote three novels based on the diaries of a recurring series graphic symbol, Moneypenny.

The grapheme—likewise known past the code number 007 (pronounced "double-O-seven")—has likewise been adapted for television, radio, comic strip, video games and moving-picture show. The films are ane of the longest continually running picture series and accept grossed over The states$7.04 billion in total, making information technology the fifth-highest-grossing moving picture serial to engagement, which started in 1962 with Dr. No, starring Sean Connery equally Bond. Every bit of 2022, there take been twenty-v films in the Eon Productions series. The most recent Bond motion-picture show, No Fourth dimension to Dice (2021), stars Daniel Craig in his fifth portrayal of Bail; he is the sixth actor to play Bond in the Eon series. In that location have besides been two independent productions of Bond films: Casino Royale (a 1967 spoof starring David Niven) and Never Say Never Once more (a 1983 remake of an earlier Eon-produced movie, 1965's Thunderball, both starring Connery). In 2022, the series was estimated to be worth $19.9 billion,[1] making James Bail 1 of the highest-grossing media franchises of all time.

The Bond films are renowned for a number of features, including the musical accessory, with the theme songs having received Academy Award nominations on several occasions, and two wins. Other important elements which run through most of the films include Bail'south cars, his guns, and the gadgets with which he is supplied by Q Branch. The films are as well noted for Bond's relationships with various women, who are popularly referred to every bit "Bond girls".

Publication history

Creation and inspiration

Ian Fleming created the fictional character of James Bond as the primal figure for his works. Bond is an intelligence officeholder in the Undercover Intelligence Service, unremarkably known every bit MI6. Bail is known by his code number, 007, and was a Royal Naval Reserve Commander. Fleming based his fictional creation on a number of individuals he came across during his time in the Naval Intelligence Sectionalisation and 30 Assault Unit during the Second Earth War, admitting that Bond "was a compound of all the secret agents and commando types I met during the war".[2] Among those types were his brother, Peter, who had been involved in backside-the-lines operations in Norway and Greece during the war.[3] Aside from Fleming's blood brother, a number of others as well provided some aspects of Bond'due south make up, including Conrad O'Brien-ffrench, Patrick Dalzel-Chore and Bill "Biffy" Dunderdale.[2]

The name James Bond came from that of the American ornithologist James Bond, a Caribbean bird expert and author of the definitive field guide Birds of the West Indies. Fleming, a cracking birdwatcher himself, had a copy of Bond'due south guide and he later explained to the ornithologist'south wife that "It struck me that this brief, unromantic, Anglo-Saxon and yet very masculine proper name was just what I needed, so a 2nd James Bond was born".[4] He further explained that:

When I wrote the offset ane in 1953, I wanted Bond to be an extremely dull, uninteresting man to whom things happened; I wanted him to be a blunt instrument ... when I was casting around for a name for my protagonist I idea past God, [James Bond] is the dullest name I ever heard.

On another occasion, Fleming said: "I wanted the simplest, dullest, plainest-sounding proper name I could find, 'James Bail' was much meliorate than something more interesting, like 'Peregrine Carruthers'. Exotic things would happen to and around him, but he would be a neutral figure—an anonymous, blunt instrument wielded by a government section."[6]

Fleming decided that Bond should resemble both American vocalizer Hoagy Carmichael and himself[7] and in Casino Royale, Vesper Lynd remarks, "Bond reminds me rather of Hoagy Carmichael, but in that location is something cold and ruthless." Likewise, in Moonraker, Special Co-operative officer Gala Make thinks that Bond is "certainly good-looking ... Rather like Hoagy Carmichael in a mode. That black hair falling down over the right eyebrow. Much the same bones. Just in that location was something a bit vicious in the mouth, and the eyes were cold."[7]

Fleming endowed Bail with many of his own traits, including sharing the same golf handicap, the taste for scrambled eggs, and using the same brand of toiletries.[8] Bond'south tastes are also often taken from Fleming's own as was his behaviour,[9] with Bond's love of golf and gambling mirroring Fleming's own. Fleming used his experiences of his career in espionage and all other aspects of his life as inspiration when writing, including using names of school friends, acquaintances, relatives and lovers throughout his books.[2]

It was not until the penultimate novel, Yous Merely Live Twice, that Fleming gave Bond a sense of family background. The book was the first to exist written after the release of Dr. No in cinemas, and Sean Connery's delineation of Bond affected Fleming's interpretation of the character, henceforth giving Bond both a dry out sense of humour and Scottish antecedents that were not present in the previous stories.[10] In a fictional obituary, purportedly published in The Times, Bond's parents were given as Andrew Bail, from the village of Glencoe, Scotland, and Monique Delacroix, from the canton of Vaud, Switzerland.[11] Fleming did not provide Bail's date of birth, simply John Pearson'south fictional biography of Bond, James Bond: The Authorized Biography of 007, gives Bond a birth engagement on xi Nov 1920,[12] while a study by John Griswold puts the appointment at 11 Nov 1921.[13]

Ian Fleming novels

Goldeneye, in Jamaica, where Fleming wrote all the Bond novels[14]

Whilst serving in the Naval Intelligence Sectionalisation, Fleming had planned to become an author[15] and had told a friend, "I am going to write the spy story to end all spy stories."[two] On 17 Feb 1952, he began writing his first James Bail novel, Casino Royale, at his Goldeneye manor in Jamaica,[16] where he wrote all his Bail novels during the months of Jan and February each year.[17] He started the story before long before his wedding to his pregnant girlfriend, Ann Charteris, in order to distract himself from his forthcoming nuptials.[18]

Afterward completing the manuscript for Casino Royale, Fleming showed it to his friend (and later editor) William Plomer to read. Plomer liked it and submitted it to the publishers, Jonathan Cape, who did non similar it as much. Greatcoat finally published it in 1953 on the recommendation of Fleming'south older brother Peter, an established travel writer.[17] Between 1953 and 1966, two years subsequently his death, twelve novels and 2 short-story collections were published, with the last two books—The Man with the Gilded Gun and Octopussy and The Living Daylights—published posthumously.[19] All the books were published in the UK through Jonathan Greatcoat.

Mail-Fleming novels

Later Fleming's expiry, a continuation novel, Colonel Sunday, was written by Kingsley Amis (as Robert Markham) and published in 1968.[34] Amis had already written a literary study of Fleming'due south Bond novels in his 1965 work The James Bond Dossier.[35] Although novelisations of two of the Eon Productions Bail films appeared in impress, James Bond, The Spy Who Loved Me and James Bail and Moonraker, both written by screenwriter Christopher Wood,[36] the series of novels did not continue until the 1980s. In 1981, the thriller author John Gardner picked up the series with Licence Renewed.[37] Gardner went on to write xvi Bond books in total; 2 of the books he wrote—Licence to Kill and GoldenEye—were novelisations of Eon Productions films of the aforementioned name. Gardner moved the Bail series into the 1980s, although he retained the ages of the characters as they were when Fleming had left them.[38] In 1996, Gardner retired from writing James Bond books due to sick health.[39]

In 1996, the American writer Raymond Benson became the author of the Bail novels. Benson had previously been the author of The James Bail Bedside Companion, first published in 1984.[54] By the time he moved on to other, non-Bond related projects in 2002, Benson had written half dozen Bail novels, iii novelisations and iii short stories.[55]

Afterwards a gap of six years, Sebastian Faulks was commissioned by Ian Fleming Publications to write a new Bond novel, which was released on 28 May 2008, the 100th anniversary of Fleming's birth.[65] The book—titled Devil May Care—was published in the UK by Penguin Books and past Doubleday in the US.[66] American writer Jeffery Deaver was and so commissioned by Ian Fleming Publications to produce Carte Blanche, which was published on 26 May 2022.[67] The book turned Bond into a post-9/eleven agent, contained of MI5 or MI6.[68] On 26 September 2022, Solo by William Boyd, prepare in 1969, was published.[69] In October 2022, it was appear that Anthony Horowitz was to write a Bond continuation novel.[70] Prepare in the 1950s two weeks afterward the events of Goldfinger, it contains fabric written, just previously unreleased, by Fleming. Trigger Mortis was released on 8 September 2022.[71] [72] [73] Horowitz's second Bond novel, Forever and a Day, tells the origin story of Bail as a 00 agent prior to the events of Casino Royale. The novel, as well based on unpublished material from Fleming, was released on 31 May 2022.[74] [75] Horowitz'south third Bail novel, With a Heed to Kill, volition be published on 26 May 2022.[76]

Immature Bond

The Young Bond series of novels was started by Charlie Higson[77] and, between 2005 and 2009, v novels and one short story were published.[78] The outset Young Bond novel, SilverFin was as well adapted and released equally a graphic novel on 2 October 2008 by Puffin Books.[79] In October 2022 Ian Fleming Publications announced that Stephen Cole would continue the series, with the first edition scheduled to be released in Autumn 2022.[fourscore]

- 2005 SilverFin [81]

- 2006 Blood Fever [82]

- 2007 Double or Dice [83]

- 2007 Hurricane Gold [84]

- 2008 By Royal Command [85] & SilverFin [86] (graphic novel)

- 2009 "A Hard Homo to Kill"[87] (curt story)

The Moneypenny Diaries

The Moneypenny Diaries are a trilogy of novels chronicling the life of Miss Moneypenny, M's personal secretary. The novels are written past Samantha Weinberg under the pseudonym Kate Westbrook, who is depicted every bit the volume's "editor".[88] The first instalment of the trilogy, subtitled Guardian Angel, was released on 10 October 2005 in the Britain.[89] A 2nd volume, subtitled Surreptitious Servant was released on 2 November 2006 in the United kingdom, published past John Murray.[90] A tertiary volume, subtitled Terminal Fling was released on ane May 2008.[91]

- 2005 The Moneypenny Diaries: Guardian Affections [92]

- 2006 Undercover Retainer: The Moneypenny Diaries [93]

- 2008 The Moneypenny Diaries: Final Fling [94]

Adaptations

Television

In 1954, CBS paid Ian Fleming $one,000 ($9,637 in 2022 dollars[95]) to conform his novel Casino Royale into a one-60 minutes idiot box hazard, "Casino Royale", as part of its Climax! series.[96] The episode aired live on 21 Oct 1954 and starred Barry Nelson as "Card Sense" James Bond and Peter Lorre as Le Chiffre.[97] The novel was adapted for American audiences to testify Bond every bit an American amanuensis working for "Combined Intelligence", while the character Felix Leiter—American in the novel—became British onscreen and was renamed "Clarence Leiter".[98]

In 1973, a BBC documentary Omnibus: The British Hero featured Christopher Cazenove playing a number of such title characters (east.g. Richard Hannay and Bulldog Drummond). The documentary included James Bond in dramatised scenes from Goldfinger—notably featuring 007 being threatened with the novel'southward circular saw, rather than the motion picture'due south laser axle—and Diamonds Are Forever.[99] In 1991, a kids'due south spin-off Television set cartoon series, James Bond Jr., was produced with Corey Burton in the role of Bond's nephew, besides called James Bond.[100]

Radio

In 1958, the novel Moonraker was adapted for broadcast on Southward African radio, with Bob Holness providing the voice of Bond.[101] [102] According to The Independent, "listeners across the Union thrilled to Bob's cultured tones as he defeated evil master criminals in search of world domination".[103]

The BBC take adjusted five of the Fleming novels for circulate: in 1990 You lot But Live Twice was adapted into a ninety-minute radio play for BBC Radio 4 with Michael Jayston playing James Bond. The production was repeated a number of times between 2008 and 2022.[104] On 24 May 2008 BBC Radio iv broadcast an adaptation of Dr. No. The thespian Toby Stephens, who played Bail villain Gustav Graves in the Eon Productions version of Die Another Solar day, played Bail, while Dr. No was played by David Suchet.[105] Following its success, a second story was adapted and on 3 April 2022 BBC Radio 4 broadcast Goldfinger with Stephens again playing Bond.[106] Sir Ian McKellen was Goldfinger and Stephens' Die Another Twenty-four hours co-star Rosamund Pike played Pussy Galore. The play was adapted from Fleming'due south novel by Archie Scottney and was directed by Martin Jarvis.[107] In 2022, the novel From Russian federation, with Beloved was dramatised for Radio 4; it featured a full cast again starring Stephens as Bond.[108] In May 2022 Stephens again played Bond, in On Her Majesty'south Hugger-mugger Service, with Alfred Molina every bit Blofeld, and Joanna Lumley as Irma Bunt.[109]

Comics

John McLusky's rendition of James Bond

In 1957, the Daily Limited approached Ian Fleming to adapt his stories into comic strips, offering him £i,500 per novel and a share of takings from syndication.[110] Afterwards initial reluctance, Fleming, who felt the strips would lack the quality of his writing, agreed.[111] To aid the Daily Express in illustrating Bond, Fleming deputed an creative person to create a sketch of how he believed James Bond looked. The illustrator, John McLusky, however, felt that Fleming's 007 looked likewise "outdated" and "pre-state of war" and inverse Bond to give him a more than masculine look.[112] The first strip, Casino Royale was published from seven July 1958 to xiii December 1958[113] and was written by Anthony Hern and illustrated by John McLusky.[114]

Most of the Bond novels and short stories have since been adapted for analogy, too as Kingsley Amis's Colonel Dominicus; the works were written by Henry Gammidge or Jim Lawrence with Yaroslav Horak replacing McClusky as artist in 1966.[113] After the Fleming and Amis textile had been adjusted, original stories were produced, continuing in the Daily Express and Sunday Limited until May 1977.[112]

Several comic book adaptations of the James Bond films take been published through the years: at the fourth dimension of Dr. No's release in October 1962, a comic volume accommodation of the screenplay, written by Norman J. Nodel, was published in U.k. as part of the Classics Illustrated anthology series.[115] It was later reprinted in the United States by DC Comics as part of its Showcase anthology series, in January 1963. This was the first American comic book appearance of James Bail and is noteworthy for being a relatively rare example of a British comic beingness reprinted in a adequately high-contour American comic. It was also one of the earliest comics to exist censored on racial grounds (some skin tones and dialogue were inverse for the American market).[116] [115]

With the release of the 1981 film For Your Eyes Simply, Marvel Comics published a two-issue comic book adaptation of the film.[117] [118] When Octopussy was released in the cinemas in 1983, Marvel published an accompanying comic;[115] Eclipse also produced a one-off comic for Licence to Kill, although Timothy Dalton refused to allow his likeness to be used.[119] New Bond stories were also drawn up and published from 1989 onwards through Curiosity, Eclipse Comics, Nighttime Horse Comics and Dynamite Entertainment.[115] [118] [120]

Films

Eon Productions films

Franchise logo, 1995–present

Eon Productions, the company of Canadian Harry Saltzman and American Albert R. "Cubby" Broccoli, released the starting time cinema accommodation of an Ian Fleming novel, Dr. No (1962), based on the eponymous 1958 novel and featuring Sean Connery as 007.[121] Connery starred in a further four films before leaving the role subsequently You Only Live Twice (1967),[122] which was taken up by George Lazenby for On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969).[123] Lazenby left the function after only one appearance and Connery was brought back for his last Eon-produced film Diamonds Are Forever.[124]

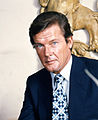

Roger Moore was appointed to the role of 007 for Alive and Let Dice (1973). He played Bond a further six times over twelve years, before being replaced by Timothy Dalton for two films. Afterwards a vi-year hiatus, during which a legal wrangle threatened Eon'due south productions of the Bond films,[125] Irish gaelic actor Pierce Brosnan was cast as Bail in GoldenEye (1995); he remained in the part for a full of four films through 2002. In 2006, Daniel Craig was given the role for Casino Royale (2006), which rebooted the serial.[126] Craig appeared for a total of v films.[127] The series has grossed well over $7 billion to appointment, making it the fifth-highest-grossing flick series.[128]

| Title | Twelvemonth | Role player | Managing director |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dr. No | 1962 | Sean Connery | Terence Immature |

| From Russia with Love | 1963 | ||

| Goldfinger | 1964 | Guy Hamilton | |

| Thunderball | 1965 | Terence Immature | |

| Y'all Only Alive Twice | 1967 | Lewis Gilbert | |

| On Her Majesty's Undercover Service | 1969 | George Lazenby | Peter R. Hunt |

| Diamonds Are Forever | 1971 | Sean Connery | Guy Hamilton |

| Alive and Let Dice | 1973 | Roger Moore | |

| The Man with the Golden Gun | 1974 | ||

| The Spy Who Loved Me | 1977 | Lewis Gilbert | |

| Moonraker | 1979 | ||

| For Your Eyes Merely | 1981 | John Glen | |

| Octopussy | 1983 | ||

| A View to a Kill | 1985 | ||

| The Living Daylights | 1987 | Timothy Dalton | |

| Licence to Impale | 1989 | ||

| GoldenEye | 1995 | Pierce Brosnan | Martin Campbell |

| Tomorrow Never Dies | 1997 | Roger Spottiswoode | |

| The World Is Non Enough | 1999 | Michael Apted | |

| Die Some other Twenty-four hour period | 2002 | Lee Tamahori | |

| Casino Royale | 2006 | Daniel Craig | Martin Campbell |

| Breakthrough of Solace | 2008 | Marc Forster | |

| Skyfall | 2012 | Sam Mendes | |

| Spectre | 2015 | ||

| No Time to Die | 2021 | Cary Joji Fukunaga[129] |

Non-Eon films

In 1967, Casino Royale was adapted into a parody Bond film starring David Niven as Sir James Bond and Ursula Andress equally Vesper Lynd. Niven had been Fleming's preference for the part of Bond.[130] The result of a courtroom example in the High Courtroom in London in 1963 allowed Kevin McClory to produce a remake of Thunderball titled Never Say Never Once more in 1983.[131] The film, produced by Jack Schwartzman's Taliafilm production company and starring Sean Connery equally Bond, was not part of the Eon series of Bond films. In 1997, the Sony Corporation acquired all or some of McClory's rights in an undisclosed deal,[131] which were and so subsequently caused past MGM, whilst on 4 December 1997, MGM announced that the company had purchased the rights to Never Say Never Once again from Taliafilm.[132] Equally of 2022[update], Eon holds the full accommodation rights to all of Fleming's Bond novels.[131] [133]

| Title | Yr | Actor | Director(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casino Royale | 1967 | David Niven | Ken Hughes John Huston Joseph McGrath Robert Parrish Val Guest Richard Talmadge |

| Never Say Never Once more | 1983 | Sean Connery | Irvin Kershner |

Music

" cocky, swaggering, confident, dark, dangerous, suggestive, sexy, unstoppable."

—David Arnold

The "James Bond Theme" was written by Monty Norman and was first orchestrated past the John Barry Orchestra for 1962'due south Dr. No, although the actual authorship of the music has been a matter of controversy for many years.[135] In 2001, Norman won £30,000 in libel damages from The Lord's day Times newspaper, which suggested that Barry was entirely responsible for the composition.[136] The theme, equally written by Norman and arranged by Barry, was described by some other Bond pic composer, David Arnold, every bit "bebop-swing vibe coupled with that vicious, dark, distorted electric guitar, definitely an musical instrument of rock 'n' curlicue ... it represented everything about the character you would want: It was self, swaggering, confident, night, dangerous, suggestive, sexy, unstoppable. And he did it in two minutes."[134] Barry composed the scores for eleven Bond films[137] and had an uncredited contribution to Dr. No with his arrangement of the Bail Theme.[134]

A Bond picture staple are the theme songs heard during their title sequences sung by well-known pop singers.[138] Several of the songs produced for the films have been nominated for Academy Awards for Original Song, including Paul McCartney'southward "Live and Let Dice",[139] Carly Simon's "Nobody Does It Amend",[140] Sheena Easton's "For Your Optics Only",[141] Adele's "Skyfall",[142] and Sam Smith's "Writing'southward on the Wall".[143] Adele won the laurels at the 85th Academy Awards, and Smith won at the 88th Academy Awards.[144] For the non-Eon produced Casino Royale, Burt Bacharach'southward score included "The Look of Beloved" (sung by Dusty Springfield), which was nominated for an Academy Award for All-time Original Song.[145]

Video games

In 1983, the first Bail video game, developed and published past Parker Brothers, was released for the Atari 2600, Atari 5200, Atari 800, Commodore 64, and ColecoVision.[146] Since then, there accept been numerous video games either based on the films or using original storylines. In 1997, the offset-person shooter video game GoldenEye 007 was developed past Rare for the Nintendo 64, based on GoldenEye.[147] The game received highly positive reviews,[148] won the BAFTA Interactive Entertainment Honor for UK Developer of the Year in 1998,[149] and sold over eight meg copies worldwide,[150] [151] grossing $250 million,[152] making it the third-best-selling Nintendo 64 game.[153] It is frequently cited every bit 1 of the greatest video games of all time.[154] [155] [156]

In 1999, Electronic Arts acquired the licence and released Tomorrow Never Dies on xvi December 1999.[157] In October 2000, they released The World Is Not Enough [158] for the Nintendo 64[159] followed by 007 Racing for the PlayStation on 21 Nov 2000.[160] In 2003, the company released James Bond 007: Everything or Cipher,[161] which included the likenesses and voices of Pierce Brosnan, Willem Dafoe, Heidi Klum, Judi Dench and John Cleese, amongst others.[162] In November 2005, Electronic Arts released a video game adaptation of 007: From Russian federation with Honey,[163] which involved Sean Connery's prototype and vox-over for Bond.[163] In 2006, Electronic Arts announced a game based on then-upcoming film Casino Royale: the game was cancelled because information technology would non be ready by the film's release in November of that year. With MGM losing revenue from lost licensing fees, the franchise was removed from EA to Activision.[164] Activision subsequently released the 007: Quantum of Solace game on 31 Oct 2008, based on the film of the same proper name.[165]

A new version of GoldenEye 007 featuring Daniel Craig was released for the Wii and a handheld version for the Nintendo DS in November 2022.[166] A year later a new version was released for Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 nether the title GoldenEye 007: Reloaded.[167] [168] In October 2022 007 Legends was released, which featured 1 mission from each of the Bond actors of the Eon Productions' series.[169] In Nov 2022, IO Interactive announced Project 007, an original James Bail video game, working closely with licensors MGM and Eon Productions.[170] [171]

Role-playing game

From 1983 to 1987, a licensed tabletop role-playing game, James Bond 007: Function-Playing In Her Majesty's Secret Service, was published by Victory Games (a branch of Avalon Colina) with it existence designed by Gerard Christopher Klug. It was the about popular espionage role-playing game for its time.[172] In addition to providing materials for players to create original scenarios, the game also offered players the opportunity to have adventures modelled after many of the Eon Productions flick adaptations, albeit with modifications to provide challenges by preventing players from slavishly imitating Bail's actions in the stories.[172]

Guns, vehicles and gadgets

Guns

For the first 5 novels, Fleming armed Bail with a Beretta 418[173] until he received a letter of the alphabet from a 30-i-yr-old Bail enthusiast and gun proficient, Geoffrey Boothroyd, criticising Fleming's option of firearm for Bail,[174] calling it "a lady'southward gun—and non a very squeamish lady at that!"[175] Boothroyd suggested that Bail should bandy his Beretta for a 7.65mm Walther PPK and this exchange of arms made it to Dr. No.[176] Boothroyd as well gave Fleming communication on the Berns-Martin triple draw shoulder holster and a number of the weapons used by SMERSH and other villains.[177] In thanks, Fleming gave the MI6 Armourer in his novels the name Major Boothroyd and, in Dr. No, M introduces him to Bond as "the greatest small-arms expert in the world".[176] Bond also used a multifariousness of rifles, including the Cruel Model 99 in "For Your Eyes Only" and a Winchester .308 target burglarize in "The Living Daylights".[173] Other handguns used by Bail in the Fleming books included the Colt Detective Special and a long-barrelled Filly .45 Army Special.[173]

The first Bond film, Dr. No, saw M ordering Bond to leave his Beretta behind and take up the Walther PPK,[178] which Bond used in eighteen films.[179] In Tomorrow Never Dies and the ii subsequent films, Bond'south chief weapon was the Walther P99 semi-automatic pistol.[179]

Vehicles

In the early Bond stories Fleming gave Bond a battleship-grey Bentley 4+ 1⁄2 Litre with an Amherst Villiers supercharger.[180] After Bond'southward car was written off by Hugo Drax in Moonraker, Fleming gave Bond a Marker Ii Continental Bentley, which he used in the remaining books of the series.[181] During Goldfinger, Bond was issued with an Aston Martin DB Mark Iii with a homing device, which he used to track Goldfinger across France. Bond returned to his Bentley for the subsequent novels.[181]

The Bond of the films has driven a number of cars, including the Aston Martin V8 Vantage,[182] during the 1980s, the V12 Beat[182] and DBS[183] during the 2000s, as well as the Lotus Esprit;[184] the BMW Z3,[185] BMW 750iL[185] and the BMW Z8.[185] He has, however, also needed to drive a number of other vehicles, ranging from a Citroën 2CV to a Routemaster Coach, amongst others.[186]

Bond's most famous automobile is the silver grayness Aston Martin DB5, first seen in Goldfinger;[187] it after featured in Thunderball, GoldenEye, Tomorrow Never Dies, Casino Royale, Skyfall and Spectre.[188] [189] The films have used a number of different Aston Martins for filming and publicity, 1 of which was sold in January 2006 at an sale in the Usa for $2.one one thousand thousand to an unnamed European collector.[190] In 2022, another DB5 used in Goldfinger was sold at auction for $iv.6m million (£2.6 million).[191]

Gadgets

The Trivial Nellie autogyro with its creator and pilot, Ken Wallis.

Fleming's novels and early screen adaptations presented minimal equipment such as the booby-trapped attaché case in From Russian federation, with Love, although this situation changed dramatically with the films.[192] Nevertheless, the effects of the two Eon-produced Bond films Dr. No and From Russia with Love had an upshot on the novel The Human being with the Gold Gun, through the increased number of devices used in Fleming's final story.[193]

For the flick adaptations of Bond, the pre-mission briefing by Q Branch became one of the motifs that ran through the serial.[194] Dr. No provided no spy-related gadgets, simply a Geiger counter was used; industrial designer Andy Davey observed that the kickoff ever onscreen spy-gadget was the attaché instance shown in From Russia with Love, which he described as "a classic 007 product".[195] The gadgets causeless a higher contour in the 1964 film Goldfinger. The movie's success encouraged further espionage equipment from Q Branch to be supplied to Bond, although the increased employ of technology led to an accusation that Bond was over-reliant on equipment, particularly in the later films.[196]

"If information technology hadn't been for Q Co-operative, you'd have been dead long ago!"

—Q, to Bail, Licence to Kill

Davey noted that "Bond's gizmos follow the zeitgeist more closely than any other ... nuance in the films"[195] as they moved from the potential representations of the future in the early films, through to the brand-name obsessions of the later films.[195] Information technology is also noticeable that, although Bond uses a number of pieces of equipment from Q Branch, including the Footling Nellie autogyro,[197] a jet pack[198] and the exploding attaché case,[199] the villains are also well-equipped with custom-made devices,[195] including Scaramanga's golden gun,[200] Rosa Klebb's poisonous substance-tipped shoes,[201] Oddjob'southward steel-rimmed bowler hat[202] and Blofeld's communication devices in his agents' vanity case.[195]

Cultural impact

Cinematically, Bail has been a major influence inside the spy genre since the release of Dr. No in 1962,[203] with 22 secret agent films released in 1966 alone attempting to capitalise on the Bond franchise's popularity and success.[204] The showtime parody was the 1964 film Comport On Spying, which shows the villain Dr. Crow being overcome past agents who included James Bind (Charles Hawtry) and Daphne Honeybutt (Barbara Windsor).[205] One of the films that reacted against the portrayal of Bond was the Harry Palmer series, whose commencement film, The Ipcress File was released in 1965. The eponymous hero of the series was what academic Jeremy Packer called an "anti-Bail",[206] or what Christoph Lindner calls "the thinking man's Bond".[207] The Palmer series were produced by Harry Saltzman, who also used key crew members from the Bail series, including designer Ken Adam, editor Peter R. Hunt and composer John Barry.[208] The four "Matt Captain" films starring Dean Martin (released betwixt 1966 and 1969),[209] the "Flintstone" serial starring James Coburn (comprising two films, one each in 1966 and 1969),[210] while The Man from U.N.C.50.East. also moved onto the movie theatre screen, with eight films released: all were testaments to Bond'south prominence in pop culture.[137] More recently, the Austin Powers series by writer, producer and comedian Mike Myers,[211] and other parodies such as the Johnny English trilogy of films,[212] accept likewise used elements from or parodied the Bond films.

Following the release of the film Dr. No in 1962, the line "Bond ... James Bond", became a catch phrase that entered the dictionary of Western pop civilization: writers Cork and Scivally said of the introduction in Dr. No that the "signature introduction would become the most famous and loved film line always".[213] In 2001, it was voted equally the "best-loved one-liner in cinema" by British movie house goers,[214] and in 2005, it was honoured equally the 22nd greatest quotation in cinema history by the American Film Institute as part of their 100 Years Series.[215] The 2005 American Film Institute's '100 Years' series recognised the character of James Bond himself every bit the third greatest picture hero.[216] He was besides placed at number eleven on a like list past Empire [217] and as the fifth greatest motion picture graphic symbol of all time past Premiere.[218]

The 24 James Bond films produced by Eon are the longest continually running film series of all time, and including the two non Eon produced films, the 26 Bond films take grossed over $7.04 billion in total, making it the sixth-highest-grossing franchise to date. It is estimated that since Dr. No, a quarter of the globe's population have seen at least one Bond picture.[219] The Britain Film Distributors' Clan have stated that the importance of the Bond series of films to the British movie industry cannot be overstated, as they "form the backbone of the manufacture".[220]

Television likewise saw the issue of Bond films, with the NBC series The Man from U.Northward.C.L.E.,[221] which was described as the "first network boob tube fake" of Bond,[222] largely because Fleming provided communication and ideas on the development of the series, fifty-fifty giving the chief character the proper noun Napoleon Solo.[223] Other 1960s television series inspired by Bail include I Spy,[210] and Become Smart.[224]

Considered a British cultural icon, James Bond had become such a symbol of the United kingdom that the grapheme, played past Craig, appeared in the opening anniversary of the 2022 London Olympics as Queen Elizabeth Ii's escort.[225] [226] From 1968 to 2003, and since 2022, the Cadbury chocolate box Milk Tray has been advertised by the 'Milk Tray Homo', a tough James Bond–mode figure who undertakes daunting 'raids' to surreptitiously deliver a box of Milk Tray chocolates to a lady.[227] [228]

Throughout the life of the film series, a number of tie-in products have been released.[229] In 2022, a James Bail museum opened atop the Austrian Alps.[230] The futuristic museum is synthetic on the summit of Gaislachkogl Mountain in Sölden at 10,000 ft (3,048 m) to a higher place bounding main level.[231] [232]

Criticisms

The James Bond character and related media have triggered a number of criticisms and reactions across the political spectrum, and are still highly debated in pop culture studies.[233] [234] Some observers accuse the Bond novels and films of misogyny and sexism.[235] [236] Geographers accept considered the role of exotic locations in the movies in the dynamics of the Cold State of war, with power struggles amid blocs playing out in the peripheral areas.[237] Other critics merits that the Bond films reflect regal nostalgia.[238] [239] No Time to Die director Cary Fukunaga has described Sean Connery'south version of Bond as 'basically a rapist'.[240]

See also

- 9007 James Bond, asteroid named after the graphic symbol

References

- ^ Adejobi, Alicia (27 October 2022). "Spectre motion-picture show: James Bond make worth £13bn off the dorsum of monster box function and DVD sales". International Business Times . Retrieved 15 Jan 2022.

- ^ a b c d Macintyre, Ben (v April 2008). "Bond – the real Bond". The Times. p. 36.

- ^ "Obituary: Colonel Peter Fleming, Author and explorer". The Times. 20 August 1971. p. fourteen.

- ^ "James Bond, Ornithologist, 89; Fleming Adopted Proper name for 007". New York Times . Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Hellman, Geoffrey T. (21 April 1962). "Bond's Creator". The New Yorker. p. 32. department "Talk of the Town". Retrieved ix September 2022.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 112.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2008, p. 67.

- ^ Macintyre 2008, p. 50.

- ^ Melt, William (28 June 2004). "Novel man". New Statesman. p. 40.

- ^ Macintyre 2008, p. 205.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 59.

- ^ Pearson 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Griswold 2006, p. 27.

- ^ Macintyre 2008, p. 208.

- ^ Lycett, Andrew (2004). "Fleming, Ian Lancaster (1908–1964) (subscription needed)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33168. Retrieved 7 September 2022. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 4.

- ^ a b Chancellor 2005, p. 5.

- ^ Bennett & Woollacott 2003, p. 1, ch 1.

- ^ Blackness 2005, p. 75.

- ^ "Casino Royale". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Live and Let Die". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Moonraker". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 16 September 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Diamonds are Forever". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "From Russia, with Dearest". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Dr. No". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Goldfinger". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "For Your Eyes Only". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Thunderball". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 Dec 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "The Spy Who Loved Me". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "On Her Majesty's Secret Service". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 Dec 2022. Retrieved 31 Oct 2022.

- ^ "You lot Only Live Twice". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "The Man with the Gold Gun". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Octopussy and The Living Daylights". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 7 September 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Colonel Sun". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d due east f "Film Novelizations". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on xviii September 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Simpson 2002, p. 58.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 149.

- ^ Ripley, Mike (ii November 2007). "Obituary: John Gardner: Prolific thriller writer backside the revival of James Bond and Professor Moriarty". The Guardian. p. 41. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "Licence Renewed". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "For Special Services". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 Dec 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Ice Breaker". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 Dec 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Role Of Honour". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Nobody Lives Forever". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 3 Nov 2022.

- ^ "No Deals Mr Bond". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved iii November 2022.

- ^ "Scorpius". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Win, Lose Or Die". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 Dec 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Brokenclaw". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "The Man From Barbarossa". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved iii November 2022.

- ^ "Expiry is Forever". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Never Send Flowers". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Seafire". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 3 Nov 2022.

- ^ "Cold". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 3 Nov 2022.

- ^ Raymond Benson. "Books – At a Glance". RaymondBenson.com . Retrieved 3 Nov 2022.

- ^ "Raymond Benson". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Simpson 2002, p. 62.

- ^ "Zero Minus Ten". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "The Facts Of Expiry". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 Dec 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Simpson 2002, p. 63.

- ^ Simpson 2002, p. 64.

- ^ "High Time To Kill". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Doubleshot". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved iii November 2022.

- ^ "Never Dream Of Dying". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 Dec 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "The Man With The Red Tattoo". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved iii November 2022.

- ^ "Faulks pens new James Bond novel". BBC News. 11 July 2007. Retrieved 3 Nov 2022.

- ^ "Sebastian Faulks". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved three Nov 2022.

- ^ "James Bond book called Menu Blanche". BBC News. 17 January 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Jeffery Deaver". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on fifteen April 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Solo Published Today". Ian Fleming Publications. 26 September 2022. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 1 Oct 2022.

- ^ Singh, Anita (ii October 2022). "James Bond's secret mission: to salvage Stirling Moss". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on x January 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ "James Bond: Pussy Galore returns in new novel". BBC News. BBC. 28 May 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ Flood, Alison (28 May 2022). "New James Bail novel Trigger Mortis resurrects Pussy Galore". The Guardian . Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ Furness, Hannah (28 May 2022). "Pussy Galore returns for new James Bond novel Trigger Mortis". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved vi Nov 2022.

- ^ "Forever and a Day". IanFleming.com. Ian Fleming Publications. 8 Feb 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ "New James Bond Novel Is a Prequel to Fleming's Offset". The New York Times. 12 Feb 2022. Archived from the original on 3 Jan 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ "New Horowitz Bond Title and Cover Revealed". IanFleming.com. Ian Fleming Publications. 16 December 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ Smith, Neil (3 March 2005). "The proper noun's Bail – Inferior Bail". BBC News . Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ "Charlie Higson". Puffin Books – Authors. Penguin Books. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ "SilverFin: The Graphic Novel". Puffin Books. Penguin Books. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ "New Young Bond Series in 2022". Ian Fleming Publications. 9 Oct 2022. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved xi October 2022.

- ^ "Young Bond: SilverFin". Puffin Books: Charlie Higson. Penguin Books. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved two November 2022.

- ^ "Young Bond: Blood Fever". Puffin Books: Charlie Higson. Penguin Books. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved two November 2022.

- ^ "Young Bond: Double or Die". Puffin Books: Charlie Higson. Penguin Books. Archived from the original on 1 November 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Young Bond: Hurricane Gilded". Puffin Books: Charlie Higson. Penguin Books. Archived from the original on 21 Nov 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Young Bond: By Imperial Command". Puffin Books: Charlie Higson. Penguin Books. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "SilverFin: The (Graphic Novel)". Puffin Books: Charlie Higson. Penguin Books. Retrieved 2 Nov 2022.

- ^ "Danger Society: The Young Bail Dossier". Puffin Books: Charlie Higson. Penguin Books. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Miss Moneypenny". Evening Standard. 14 Oct 2005. p. ten.

- ^ O'Connell, John (12 October 2005). "Books – Review – The Moneypenny Diaries – Kate Westbrook (ed) – John Murray GBP 12.99". Time Out. p. 47.

- ^ Weinberg, Samantha (eleven Nov 2006). "Licensed to thrill". The Times. p. 29.

- ^ Saunders, Kate (10 May 2008). "The Moneypenny Diaries: Final Fling". The Times. p. 13.

- ^ "Guardian Affections". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on viii October 2022. Retrieved two November 2022.

- ^ "Hugger-mugger Retainer". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on eight October 2022. Retrieved two November 2022.

- ^ "Final Fling". The Books. Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved two November 2022.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Existent Coin? A Historical Price Index for Use every bit a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Existent Coin? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the Usa (PDF). American Antiquarian Gild. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Toll Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved i January 2022.

- ^ Black 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. eleven.

- ^ Black 2005, p. 101.

- ^ "Radio Times". vi–12 October 1973: 74–79.

- ^ Svetkey, Benjamin (29 May 1992). "Sweet Baby James". Entertainment Weekly . Retrieved iv November 2022.

- ^ "Book Review: The Many Lives of James Bail". James Bond Radio. 18 November 2022. Retrieved four December 2022.

- ^ Edlitz, Mark (2019). The Many Lives of James Bail: How the Creators of 007 Take Decoded the Superspy. Lyons Press. p. 148. ISBN978-1493041565.

- ^ Roberts, Andrew (eight November 2006). "The Bond bunch". The Independent. p. 14.

- ^ "James Bond – Yous Only Alive Twice". BBC Radio iv Extra. BBC. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ "007 villain to play Bond on radio". BBC. 2 May 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ Hemley, Matthew (13 Oct 2009). "James Bond to return to radio as Goldfinger is adapted for BBC". The Phase Online. Retrieved xix March 2022.

- ^ "Goldfinger". Saturday Play. BBC. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Saturday Drama: From Russian federation With Dearest". BBC Radio iv. BBC. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "Saturday Drama: On Her Majesty's Secret Service". BBC. BBC. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Jütting 2007, p. 6.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 316.

- ^ a b Simpson 2002, p. 21.

- ^ a b Fleming, Gammidge & McLusky 1988, p. 6.

- ^ Jütting 2007, p. seven.

- ^ a b c d Conroy 2004, p. 293.

- ^ Evanier, Mark (3 December 2006). "Secrets Behind the Comics". NewsFromme.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 131.

- ^ a b Thompson, Frankenhoff & Bickford 2022, p. 368.

- ^ "Bond Violence Gets Artistic 'Licence'". The Palm Beach Post. 28 July 1989.

- ^ "How Dynamite's New James Bail Comic Creates a 007 We Oasis't Seen Before". Screencrush. six November 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ Sutton, Mike. "Dr. No (1962)". Screenonline. British Motion-picture show Institute. Archived from the original on iii March 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "You lot Only Live Twice". TCM. Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Retrieved two August 2022.

- ^ "On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969)". Screenonline. British Moving-picture show Institute. Retrieved 4 Nov 2022.

- ^ Feeney Callan 2002, p. 217.

- ^ Simpson 2002, p. 81.

- ^ Robey, Tim (12 January 2022). "Sam Mendes may have issues directing new James Bond flick". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Pallotta, Frank. "Daniel Craig confirms return equally James Bond". CNNMoney . Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "Motion-picture show Franchises". The Numbers. Nash Information Services. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "James Bond: Cary Joji Fukunaga to straight next Bond moving-picture show". BBC News . Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Macintyre 2008, p. 202.

- ^ a b c Poliakoff, Keith (2000). "License to Copyright – The Ongoing Dispute Over the Ownership of James Bond" (PDF). Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal. Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. 18: 387–436. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2022. Retrieved three September 2022.

- ^ "Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc. announces acquisition of Never Say Never Once again James Bond assets" (Press release). Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. 4 December 1997. Archived from the original on 5 May 2008. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Shprintz, Janet (29 March 1999). "Big Bond-holder". Variety . Retrieved iv November 2022.

Estimate Rafeedie ... found that McClory'south rights in the "Thunderball" cloth had reverted to the estate of Fleming

- ^ a b c Burlingame, Jon (3 November 2008). "Bond scores establish superspy template". Daily Variety . Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Lindner 2009, p. 122.

- ^ "Monty Norman sues for libel". Bond theme writer wins damages. BBC News. 19 March 2001. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ a b Chapman 2009, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Simpson 2002, p. 224.

- ^ "The 46th University Awards (1974) Nominees and Winners". Oscar Legacy. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ "The 50th University Awards (1978) Nominees and Winners". Oscar Legacy. Academy of Motility Movie Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 27 Oct 2022.

- ^ "The 54th Academy Awards (1982)". Oscar Legacy. Academy of Motion Picture show Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ "2013 Oscars Nominees". oscars. Jan 2022. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 10 Jan 2022.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (14 January 2022). "Oscar Nominations: The Consummate List". The Hollywood Reporter . Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Copsey, Rob (29 February 2022). "Sam Smith wins Oscar for his James Bond Spectre theme song". Official Charts Company. Retrieved vii May 2022.

- ^ "The 40th University Awards (1968)". Oscar Legacy. Academy of Film Arts and Sciences. Retrieved iv November 2022.

- ^ Backe, Hans-Joachim. "Narrative Feedback: Computer games, comics, and the James Bond Franchise" (PDF). Ruhr University Bochum. Retrieved fourteen November 2022.

- ^ Greg Sewart. "GoldenEye 007 review". Gaming Historic period Online. Archived from the original on half-dozen Oct 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "GoldenEye 007 Reviews". gamerankings.com. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Rare: Visitor". Microsoft Corporation. Archived from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Martin Hollis (ii September 2004). "The Making of GoldenEye 007". Zoonami. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Microsoft Acquires Video Game Powerhouse Rare Ltd". Microsoft News Center. 24 September 2002. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Crandall, Robert Due west.; Sidak, J. Gregory. "Video Games: Serious Business for America'southward Economic system" (PDF). Entertainment Software Association. pp. 39–40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Serafino, Jay (26 September 2022). "10 Game-Irresolute Facts About the Nintendo 64". Mental Floss. Dennis Publishing. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "The 50 best games". The Age. half-dozen October 2005. Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved nine March 2022.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Games Of All Fourth dimension". www.empireonline.com. Empire. 2009. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022.

- ^ "We rank the 100 greatest videogames". Entertainment Weekly. 13 May 2003. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "007: Tomorrow Never Dies". IGN. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved iv November 2022.

- ^ King & Krzywinska 2002, p. 183.

- ^ "The World Is Not Enough". Video Games. Eurocom Developments. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "007 Racing Review". IGN. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved four November 2022.

- ^ "James Bail 007: Everything or Zip". IGN. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "James Bail 007: Everything or Aught Review". IGN. eighteen February 2004. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 4 Nov 2022.

- ^ a b "From Russia With Love Review". IGN. Archived from the original on sixteen August 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Fritz, Ben (3 May 2006). "Bond, Superman games on the move". Variety . Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "James Bail: Quantum of Solace Reviews". CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on eighteen July 2022. Retrieved eleven Dec 2022.

- ^ Harris, Craig. "GoldenEye Reimagined for Wii". IGN. Archived from the original on eighteen June 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Walton, Mark (xx July 2022). "GoldenEye 007: Reloaded First Impressions". GameSpot . Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ Robinson, Andy (xx July 2022). "News: GoldenEye HD is official: Motility, Online Confirmed – Trailer". ComputerAndVideoGames.com. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Leif (24 Oct 2022). "007 Legends Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 28 October 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ Skrebels, Joe (19 November 2022). "Hitman Developer Announces New Bond Game, Project 007". IGN . Retrieved 19 Nov 2022.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (19 November 2022). "Hitman programmer IO is making a James Bond game". Eurogamer . Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ a b Lawrence Schick (1991). Heroic Worlds: A History and Guide to Role-Playing Games. New York: Prometheus Books. p. 63. ISBN978-0879756536.

- ^ a b c Benson 1988, p. 265.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 160.

- ^ "Bail'due south unsung heroes: Geoffrey Boothroyd, the real Q". The Daily Telegraph. 21 May 2009. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 6 Nov 2022.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2008, p. 132.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. fifteen.

- ^ Blackness 2005, p. 94.

- ^ a b Cork & Stutz 2007, p. 265.

- ^ Benson 1988, pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b Benson 1988, p. 63.

- ^ a b Cork & Stutz 2007, p. 183.

- ^ Cork & Stutz 2007, p. 182.

- ^ Cork & Stutz 2007, p. 202.

- ^ a b c Cork & Stutz 2007, p. 186.

- ^ Cork & Stutz 2007, p. 175.

- ^ Cork & Stutz 2007, p. 180.

- ^ Cork & Stutz 2007, pp. 180–181.

- ^ French, Philip (28 October 2022). "Skyfall – review". The Observer. London. p. 32.

- ^ "James Bond machine sold for over £1m". BBC News. 21 January 2006. Retrieved vi November 2022.

- ^ Andrew English language (28 October 2022). "James Bond Aston Martin DB5 sells for 拢2.6m". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ Jenkins, Tricia (September 2005). "James Bond's "Pussy" and Anglo-American Common cold War Sexuality". The Journal of American Culture. 28 (3): 309–317. doi:x.1111/j.1542-734X.2005.00215.x.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 234.

- ^ Lindner 2009, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e Davey, Andy (3 October 2002). "Left to his own devices" (abridged from print copy). Blueprint Week . Retrieved vii November 2022.

- ^ Lindner 2009, p. 169.

- ^ Cork & Stutz 2007, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Jütting 2007, p. 128.

- ^ Cork & Stutz 2007, p. 221.

- ^ Jütting 2007, p. 77.

- ^ Griswold 2006, p. 41.

- ^ Black 2005, p. 117.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Moniot, Drew (Summer 1976). "James Bond and America in the Sixties: An Investigation of the Formula Film in Popular Culture". Journal of the Academy Film Association. University of Illinois Press. 28 (3): 25–33. JSTOR 20687331.

- ^ Angelini, Sergio. "Carry On Spying (1964)". BFI Screenonline. British Flick Found. Retrieved four November 2022.

- ^ Packer 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Lindner 2009, p. 128.

- ^ "Ipcress File, The (1965)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ Allegretti, Joseph. "James Bail and Matt Captain: The Moral Universe of Literature's Most Famous Spy and His Principal American Rival" (PDF). The Mid-Atlantic Almanack. Mid-Atlantic Pop/American Civilisation Association. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ a b Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 210.

- ^ Lindner 2009, p. 76.

- ^ Howell, Peter (21 October 2022). "Thunderbollocks". Toronto Star. p. E2.

- ^ Cork & Scivally 2002, p. half dozen.

- ^ "James Bond tops motto poll". BBC News. 11 June 2001. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "100 Years Series: "Film Quotes"" (PDF). AFI 100 Years Series. American Film Plant. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2022. Retrieved 4 Nov 2022.

- ^ "100 years series: 100 heroes and villains" (PDF). AFI 100 Years Series. American Moving-picture show Manufacture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2022. Retrieved eight June 2022.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Moving picture Characters: xi. James Bond". Empire . Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ "100 Greatest Picture show Characters of All Time". Premiere . Retrieved eight June 2022.

- ^ Dodds, Klaus (2005). "Screening Geopolitics: James Bond and the Early Common cold War films (1962–1967)". Geopolitics. 10 (2): 266–289. doi:10.1080/14650040590946584. S2CID 144363319.

- ^ "British film classics: Dr No". BBC News. 21 Feb 2003. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Grigg, Richard (Nov 2007). "Vanquishing Evil without the Help of God: The Man from U.N.C.50.E. and a World Come of Age". Journal of Advice & Faith. 30 (ii): 308–339.

- ^ Worland, Rick (Winter 1994). "The Man From U.N.C.L.Eastward. and TV espionage in the 1960s". Journal of Popular Flick & Television. 21 (4): 150–162. doi:ten.1080/01956051.1994.9943983.

- ^ Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 209.

- ^ Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 211.

- ^ Brown, Nic (27 July 2022). "How James Bail whisked the Queen to the Olympics". BBC News . Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ "Action & Mystery exhibition inspired by Keen British icons". Gov.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland. one November 2022.

- ^ "Equally Cadbury's Milk Tray Man returns, which other Goggle box advertising characters are ripe for a makeover?". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on x Jan 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "Milk Tray man to swing back into activity for new Cadbury campaign". The Guardian . Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ Simpson 2002, p. 273.

- ^ "James Bond museum opens atop the Austrian Alps". TODAY.com . Retrieved eighteen July 2022.

- ^ TravelTriangle (15 June 2022). "'Die Another Day', Every bit This New James Bond Museum On The Austrian Alps Is Too Good To Be Missed". Retrieved eighteen July 2022.

- ^ "James Bail museum opens atop the Austrian Alps". NBC News . Retrieved xviii July 2022.

- ^ Lindner, Christoph (2003). The James Bail Phenomenon: A Critical Reader. Manchester Academy Press. ISBN978-0-7190-6541-5.

- ^ Comentale, Edward P.; Watt, Stephen; Willman, Skip (2005). Ian Fleming & James Bond: The Cultural Politics of 007. Indiana University Printing. ISBN978-0-253-34523-3.

- ^ "Why I'1000 Still Shaken and Stirred by James Bond". Faddy . Retrieved 13 November 2022.

I empathise the criticisms levied at the franchise. Bond is a caveman with an Omega, a misogynist with gadgets, a animate being in a tux.

- ^ Dodds, Klaus (three July 2022). "Shaking and Stirring James Bond: Age, Gender, and Resilience in Skyfall (2012)". Journal of Pop Film and Idiot box. 42 (3): 116–130. doi:10.1080/01956051.2013.858026. ISSN 0195-6051. S2CID 145499529.

- ^ Dodds, Klaus (ane July 2005). "Screening Geopolitics: James Bail and the Early Cold State of war films (1962–1967)". Geopolitics. x (two): 266–289. doi:ten.1080/14650040590946584. ISSN 1465-0045. S2CID 144363319.

- ^ Müller, Timo (2015). "The Bonds of Empire: (Postal service-)Imperial Negotiations in the 007 Film Series". In Buchenau, Barbara; Richter, Virginia (eds.). Postal service-Empire Imaginaries? Anglophone Literature, History, and the Demise of Empires. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 305–326. doi:10.1163/9789004302280_014. ISBN978-9004302280.

- ^ Jr, Marouf Hasian (20 Oct 2022). "Skyfall, James Bail's Resurrection, and 21st-Century Anglo-American Imperial Nostalgia". Advice Quarterly. 62 (5): 569–588. doi:10.1080/01463373.2014.949389. ISSN 0146-3373. S2CID 143363641.

- ^ "James Bond was 'basically' a rapist in early films, says No Time to Die director". The Guardian. 23 September 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

Bibliography

- Bennett, Tony; Woollacott, Janet (2003). "The Moments of Bond". In Lindner, Christoph (ed.). The James Bond Miracle: a Disquisitional Reader. Manchester University Press. ISBN978-0-7190-6541-five.

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN978-1-85283-233-9.

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN978-0-8032-6240-9.

- Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. London: John Murray. ISBN978-0-7195-6815-2.

- Chapman, James (2009). Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films. New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN978-1-84511-515-nine.

- Conroy, Mike (2004). 500 Corking Comicbook Action Heroes. London: Chrysalis Books Group. ISBN978-1-84411-004-ix.

- Cork, John; Scivally, Bruce (2002). James Bail: The Legacy . London: Boxtree. ISBN978-0-7522-6498-1.

- Cork, John; Stutz, Collin (2007). James Bond Encyclopedia. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN978-i-4053-3427-three.

- Feeney Callan, Michael (2002). Sean Connery . London: Virgin Books. ISBN978-ane-85227-992-ix.

- Fleming, Ian; Gammidge, Henry; McLusky, John (1988). Octopussy. London: Titan Books. ISBNi-85286-040-5.

- Griswold, John (2006). Ian Fleming's James Bond: Annotations And Chronologies for Ian Fleming'southward Bond Stories. AuthorHouse. ISBN978-ane-4259-3100-one.

- Jütting, Kerstin (2007). "Abound Up, 007!" – James Bond Over the Decades: Formula Vs. Innovation. Grin Verlag. ISBN978-3-638-85372-nine.

- King, Geoff; Krzywinska, Tanya (2002). Screenplay: movie house/videogames/interfaces. Wallflower Press. ISBN978-1-903364-23-nine.

- Lindner, Christoph (2009). The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester Academy Press. ISBN978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Lycett, Andrew (1996). Ian Fleming. London: Phoenix. ISBN978-one-85799-783-v.

- Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Your Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN978-0-7475-9527-iv.

- Packer, Jeremy (2009). Hugger-mugger agents: popular icons beyond James Bond. Peter Lang. ISBN978-0-8204-8669-vii.

- Pearson, John (2008). James Bond: The Authorized Biography. Random Business firm. ISBN978-0-09-950292-0.

- Pfeiffer, Lee; Worrall, Dave (1998). The Essential Bond. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN978-0-7522-2477-0.

- Simpson, Paul (2002). The Rough Guide to James Bail. Rough Guides. ISBN978-one-84353-142-five.

- Smith, Jim; Lavington, Stephen (2002). Bond Films . London: Virgin Books. ISBN978-0-7535-0709-4.

- Thompson, Maggie; Frankenhoff, Brent; Bickford, Peter (2010). Comic Volume Price Guide 2022. Krause Publications. ISBN978-1-4402-1399-i.

External links

| | Wikimedia Eatables has media related to James Bond. |

- Ian Fleming Publications website

- Young Bond Official Website

- Pinewood Studios Albert R. Broccoli 007 Stage website

- James Bond on IMDb

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Bond

Posted by: visserlicedle.blogspot.com

0 Response to "which james bond movie had the same name as a british national lottery draw?"

Post a Comment